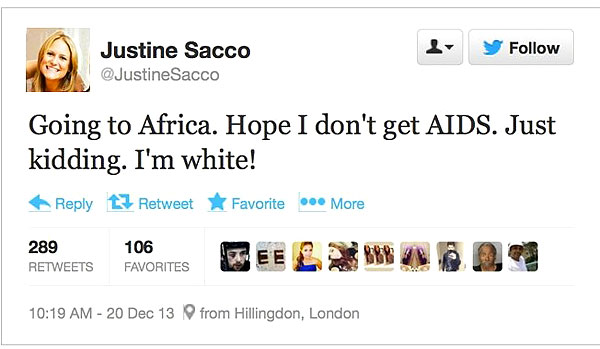

Social Media moves at light speed. Every new idea or cool marketing idea is quickly digested and forgotten for the next big thing. This is just as true when it comes to controversy. Does anyone remember Justine Sacco? For someone that created such a buzz, no one seems to be talking about her anymore.

As a quick refresher, Sacco was a high-level PR executive who tweeted out the above missive before heading to Cape Town, South Africa for vacation. During her long flight from LA to Africa, the tweet went viral. After Sacco landed, she was promptly fired from her company, and she issued an apology for her comment.

And then we all sort of forgot about it. At least, I did. I wrote it off as yet another Alicia Ann Lynch incident and moved on to the next big thing. But Justine started nagging at me as the weeks passed. As an apparently white male in my 30’s, I have an unparalleled level of privilege most others cannot imagine—even in the United States. Perhaps it was so easy for me to move on because I wasn’t that affected. I’m not a person of color.

Once I became aware of my own ignorance, I knew I needed to write something about race in social media. The main issue was where to start. Just one which Google search brought up an army of incidents like Justine Sacco. But I didn’t want to just throw up news clips about racial discrimination. The only reasonable thing for me to do was reach out to people I knew, and ask about their experiences on social media. Some of them wanted to be named, and others did not. I will respect that. Of course, once I addressed the white elephant in the room, things only seemed to get bigger. While I was interviewing people for this piece, two racially charged issues happened right in my backyard on social media. I’ll get to those in a moment.

#NotYourAsianSidekick was created by 23 year-old freelance writer Suey Park in order to start a conversation about feminism and stereotypes in the Asian community. Suey didn’t expect the hashtag to become a trending topic on Twitter, with thousands using it and commenting on the subject. Perhaps most surprising was the amount of Caucasians and Asians speaking out against Suey, telling her she was going about change in the wrong way.

I talked to my fellow colleague Debasree Ghosh about her experiences as an Indian American on social media sites like Tumblr, Pinterest, and Instagram. “There is always instances of racism on social media,” said Ghosh, remarking on when she has targeted because of her race on these sites. However, Ghosh has had a generally good experience on social media, explaining that there have always been other people of color to offer support and understanding. “There are a lot of Asians on [social media] and I know I’m not the only one going through this,” she says. “Racism will always be out there. The thing is that you should learn not to be affected by it.”

As a white person, I’d like to believe it is that easy when it comes to social media and race. Unfortunately, it’s just not the case for everyone, and I’m not so sure it should be. Perhaps we need to be affected by it. The subject just gets murkier from here.

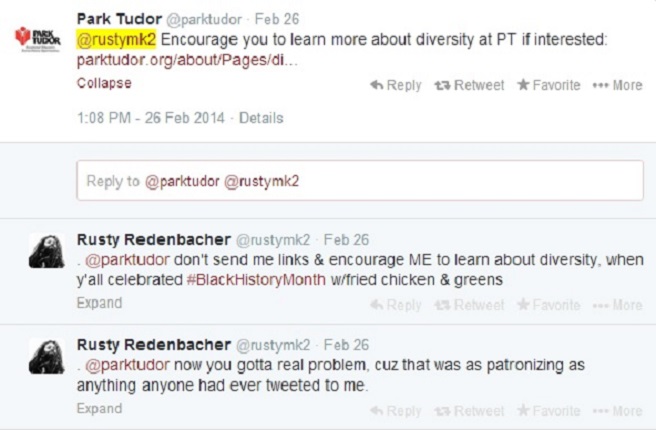

Park Tudor (a private school in Indianapolis) decided to have a special menu for Black History Month. The private school served fried chicken and collard greens as part of what they considered a program of cultural diversity. This caused a large amount of outrage from African American students and those in the community. Among them was local musician Rusty Redenbacher, who engaged in a series of hot tweets directly with the school.

Park Tudor later apologized to Redenbacher and the community, but this doesn’t change the fact that as of 2014, people are still serving fried chicken when they think of African Americans. When I asked Redenbacher if he sees much racism on social media, he had the following to say:

Every. Damn. Day. It’s no different than real life, man. There’s still human beings composing thoughts and directing them towards people. Racism is just a part of life in America. Why wouldn’t it be a part of social media?

–Rusty Redenbacher

I knew racism in America was alive and well (I have the internet), but I sort of blindly hoped it wasn’t such a part of everyday life for the people I know who aren’t white. But as I continued to read Redenbacher’s responses to my questions, the truth was becoming clear. The elephant in the room was getting heavier.

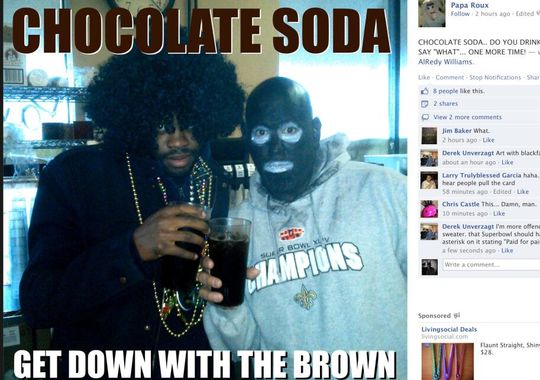

Papa Roux is a local, popular destination in Indianapolis for Cajun food. On Fat Tuesday, owner Art Bouvier sent out the following picture of himself with a customer.

Bouvier immediately began receiving criticism on social media for the picture, which he brushed off… at first. After the complaints continued, the Papa Roux owner claimed to have every right to wear Black Face due to his heritage, and his involvement with Mardi Gras and the Zulu tradition of wearing such make-up. A lot of former fans didn’t accept the explanation, and Bouvier later apologized for offending people, but not for his actions.

For the sake of some journalistic integrity, I will admit that I interviewed all my contacts well before this issue happened, but I could not go without addressing this event in a blog about race and social media. I don’t think there is any question about blatant racism on social media. Like the classic definition of pornography, everyone knows it when they see it, even if they can’t define it immediately. The problems come when we start talking about institutional racism and the basic misunderstandings of the privileged. Redenbacher again: “I really hafta weigh my words. I try not to jump on stories without checking them out first. I’m only flying the flag for things I believe in in the hopes that somehow, someway, I can influence someone to join the charge.”

So the problem seems to be that a few haven’t joined the movement. A few smaller institutions continue to be culturally insensitive, but we’d never see something like that from Silicon Valley, right?

Brogrammers is a much debated term and often hated by those near the subject. A “brogrammer” refers to an IT or social media male that engages in a frat house mentality instead of the typical nerdy stereotype most programmers are put under. People in IT and social media—usually white males if you do a quick Google search—really hate this term and bemoan anyone that uses it.

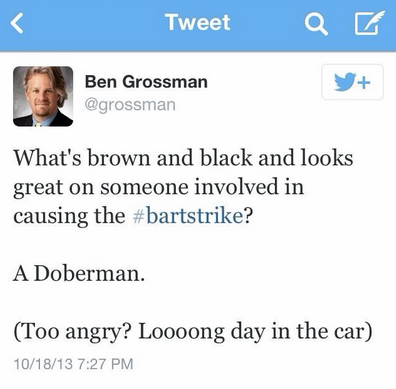

But is there any real call to use the term? Late last year a Twitter executive said that “whoever caused” a nearby transportation strike should be thrown to the dogs. Less than two months later, a start-up CEO called the local homeless population “trash” that should keep to itself. I’m not sure what is more privilege-related than calling the lower class trash and saying that people striking should be fed to dogs.

“You learn more about your friends, family, [and] colleagues via social media outlets as opposed to face to face discussions,” says Rayfield Johnson, an African-American in his late twenties who works in the computer science field. “There have been a lot of instances of racism (direct and indirect) from my experience on the social media websites.” Johnson appreciates using social networking sites like Facebook and LinkedIn, but considers them tools to keep in touch with friends and colleagues. Like Rusty Redenbacher, Johnson looks at social media as a microcosm of the world at large.

I couldn’t make any true demands about regulation of the social media sites, as that would negate the premise of what it was built on. Social Media is what it is, and should be taken as that. As a person who works in the IT field, I don’t put much blame into the tool itself, as the issues that result in such tools are usually ‘user error.’

–Rayfield Johnson

I want to believe those human errors are small and isolated, but in doing my research and talking to three reasonably different people of color about their experiences on social media sites, I came to one conclusion: All three had dealt directly with intentional racism. What does that mean? Perhaps we all don’t really comprehend what it means when someone like Justine Sacco quips about race in such a casual way. She’s most likely doing it because she’s been allowed to up until now. In fact, that is exactly the case. The PR executive had tweeted wildly culturally insensitive content before the Cape Town event.

But I don’t want to demonize Sacco or anyone else, even though that’s what Twitter did, however briefly. She is a product of her environment. It’s dangerous to mark someone like her as an “other.” By separating Sacco from the rest of our community, it allows us to believe we are above or beyond that standard of thinking. And all evidence so far is pointed to the contrary.

So what can we do? In the midst of unintended and deeply, painfully intentional racism on our social platforms, how can any of us help? Believe it or not, I’m not thinking about the power of love. It’s ironic that we have so many tools to talk to each other, but we rarely seem to use them for real communication.

I believe one day racism will be a thing of the past. And I don’t mean to say that we should all go post-race and forget about the events of the past. I mean that there will literally be a time when people no longer care about ethnic backgrounds or skin color. I also believe we can hasten that day by using all these powerful social media sites we are plugged into. Mark Twain once said that travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness. When the world is so small and accessible, how are we not all accomplished travelers? But perhaps Rusty Redenbacher says it best: “I’m thankful to talk WITH anyone that is willing to listen. There’s a big difference between talking TO people and talking WITH them.”

Thank you for reading. It was my primary intention to present these people with the utmost respect and dignity. If you liked what you read, please feel free to comment below, or send me a message on Twitter.